For much of the post–Cold War era, Africa occupied a paradoxical space in global discourse: hyper-visible in humanitarian imagery, policy briefs, and development reportage, yet absent from the geopolitical imaginary. Its visibility was shaped by the racializing, touristic gaze bell hooks critiqued in the Writing Culture cover — one that aestheticized Black and non-Western subjects while preserving Western epistemic hierarchies. Popular media such as National Geographic reinforced this optic, exoticizing landscapes and peoples into consumable images rather than political interlocutors, staging Africa as an object of administration and pity rather than as a site of thought, contestation, or strategy.

This representational order mirrors the literary grammar Chinua Achebe exposed in critiquing Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which cast Africa as a metaphysical backdrop for European self-reflection, silencing African voices while projecting primitivism. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart counters this, refusing colonial storytelling monopolies and asserting that African societies possess complex ethical, political, and epistemic life independent of imperial narratives. By challenging both literary tradition and the infrastructure of Western imagination, Achebe’s intervention continues to resonate, shaping contemporary debates about Africa’s agency, knowledge production, and its position within a resurgent geopolitical imaginary.

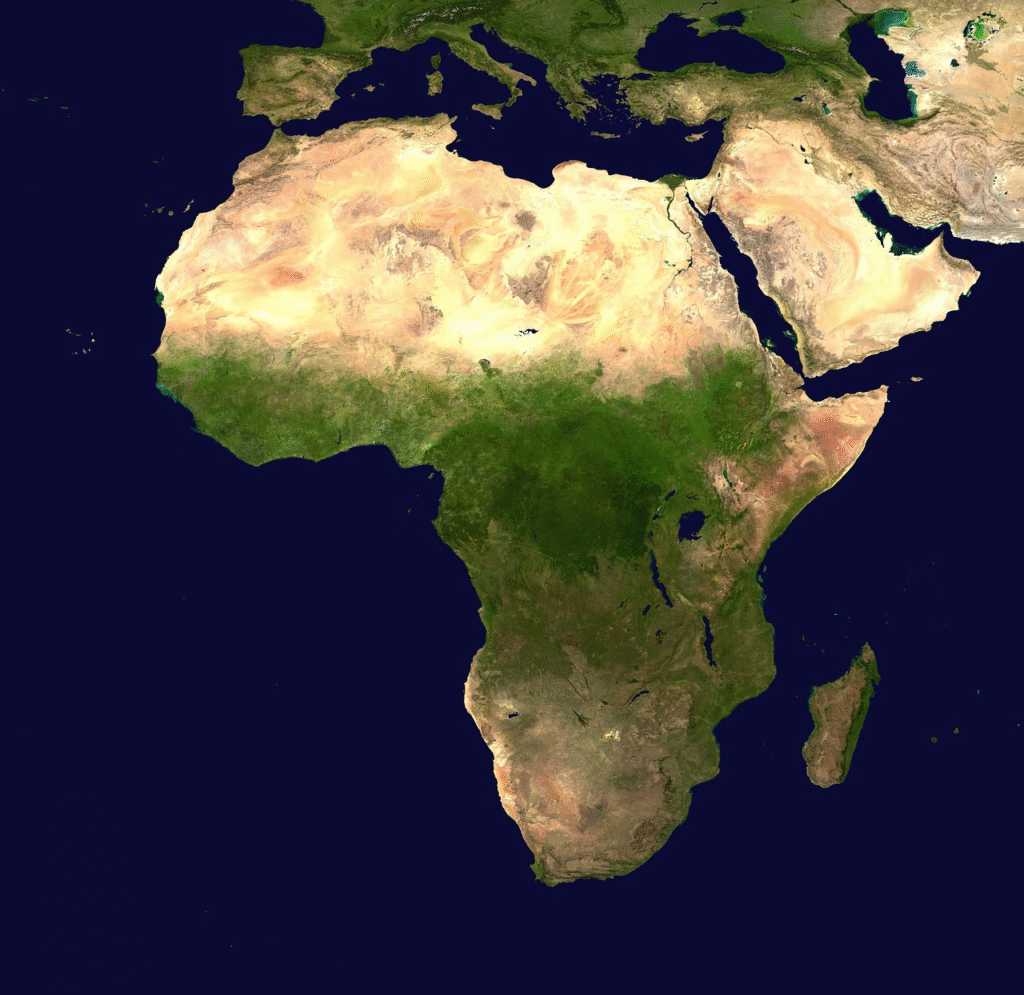

Africa is no longer just a canvas for intervention but a decisive terrain where competing global orders collide. This emerging centrality, however, is not synonymous with emancipation. Sovereignty remains entangled with regimes of extraction, debt, and the uneven allocation of vulnerability. The new scramble for minerals and alliances often overlays older cartographies of dispossession with updated idioms of partnership and modernization. Africa’s prominence thus marks a profound shift from being a managed periphery to a contested center, demanding analysis that resists celebratory narratives and interrogates how power, representation, and vulnerability remain intertwined in a pluralizing world system.

This structural shift is most tangibly evident in the diplomatic arena. The continent’s strategic discretion became globally salient following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when several key African states, including South Africa, Senegal, and Uganda, abstained from or resisted Western-led UN resolutions. This collective stance was less about support for Moscow and more a calculated assertion of non-aligned, interest-based foreign policy. It was shaped by historical skepticism of Western interventionism, complex bilateral trade ties, and primary concerns over regional food and energy security. As analyzed by the International Crisis Group, this moment forced a stark recalibration in capitals from Washington to Brussels, proving that African votes could no longer be assumed but must be actively negotiated. This newfound leverage is a direct function of multipolar competition, where African states can engage with multiple power centers. It demonstrates that Africa’s agency is now a variable that actively shapes, rather than merely responds to, the contours of international consensus.

Institutional recognition has followed this diplomatic assertiveness. The African Union‘s accession to permanent membership in the G20 in 2023 is a landmark formalization of the continent’s structural economic relevance. This seat at the table moves beyond symbolism; it provides a consolidated platform to influence critical macroeconomic negotiations, particularly regarding debt sustainability and climate finance. For instance, at subsequent summits, African representatives have successfully tabled the issue of “climate-proofing” sovereign debt, arguing that loans for infrastructure must account for vulnerability to climate shocks.

This positions Africa not as a passive recipient of global financial norms but as a potential architect of new, more equitable rules for climate-vulnerable economies. Furthermore, the AU’s presence allows the continent to frame issues like illicit financial flows and technology transfer as matters of strategic negotiation rather than developmental appeal, leveraging its collective market size and resource base as a new form of institutional capital.

Credit: https://pixabay.com/

The assertion of strategic autonomy is perhaps most visceral in the security realm, particularly across the Sahel. The cascade of French military withdrawals from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger between 2022 and 2024 marked the unceremonious end of a decades-long Françafrique security paradigm. As reported by Reuters, this was not merely a loss of European influence but a conscious, often populist-driven, expulsion by African juntas and governments asserting sovereignty.

The subsequent turn to alternatives — including contracts with Russian-linked private military companies and deepened agreements with Türkiye and Iran — represents a fraught but calculated recalibration. These partnerships, while raising serious concerns over human rights, are explicitly framed by Sahelian capitals as less paternalistic and more responsive to immediate counter-insurgency demands. This transition fundamentally restructures the regional security landscape, revealing that African governments are actively testing the market for security partners and that Western engagement is now contingent on perceived legitimacy and mutual benefit, not historical precedent.

Underpinning and intensifying this geopolitical repositioning is Africa’s irreversible demographic significance in the 21st century. The continent’s population dynamics have shifted from a subject of developmental concern to a primary driver of global economic and strategic planning. With a population projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050 and a median age under 20, Africa’s youth bulge stands in stark contrast to aging societies elsewhere. This demographic weight is reshaping global migration, labor markets, and consumption. Europe’s proactive integration of African labor — exemplified by Germany’s Skilled Immigration Act targeting healthcare and IT workers — signals a move from fearing a “migration crisis” to managing a demographic necessity. These policies create deep interdependencies, making European social welfare and economic growth directly linked to African demographic trends and bilateral cooperation.

Simultaneously, the Gulf’s economic modernization is built and serviced by millions of workers from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan. This reliance embeds African states as critical stakeholders in Gulf security and political stability. Domestically, rapid urbanization is creating a network of megacities like Lagos and Nairobi, which are becoming crucibles of innovation and cultural production. A young, digitally native population influences global trends in music, fintech, and social activism. The economic power of the diaspora, which sent over $100 billion in remittances to sub-Saharan Africa in 2023, creates powerful transnational constituencies. Consequently, Africa’s demographic trajectory is now a mandatory variable in the long-term strategic planning of every major power, a fact underscored by policy frameworks like the European Union’s Joint Vision with Africa.

This demographic and political agency intersects powerfully with Africa’s role as the repository of the world’s critical energy transition minerals. Cobalt, lithium, and platinum group metals concentrated in the DRC, Zambia, and South Africa are strategic assets in the geopolitical competition for green industrial supremacy. The old model of raw extraction is being contested. African governments are leveraging this demand to enforce local beneficiation policies. Namibia’s ban on the export of unprocessed lithium and critical minerals is a pioneering case, forcing foreign investors to build local refining capacity.

Similarly, the DRC and Zambia are advancing a joint initiative for battery manufacturing. These actions, covered by outlets like The Africa Report, transform Africa from a passive supplier into an active negotiator setting terms for global industrial policy. This shift is altering investment treaties, as external powers must now offer technology transfer and industrial cooperation to secure access.

Infrastructure development mirrors this pattern of strategic navigation. The continent has become a canvas for competing models of global connectivity, from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). African governments engage in “multi-vector infrastructure diplomacy,” pitting proposals against each other to secure better terms, demand co-financing, and insist on higher local content. The standard-gauge railway in Kenya, initially a flagship BRI project, has seen renegotiations and engagements with other partners for extensions, illustrating this pragmatic, interest-driven approach to avoid over-reliance on a single creditor and maximize national benefit.

Ultimately, Africa’s resurgence exposes the profound contradictions of the existing liberal international order. Calls for a “rules-based system” sound hollow to African capitals confronting unmet climate finance pledges and a UN Security Council where they have no permanent voice. The collective drive for “strategic autonomy” is a pragmatic adaptation to a contested, multipolar world. It reflects the understanding that agency is now derived from the ability to selectively engage with all sides, leveraging resources, votes, and geographic position to extract concessions.

The continent’s financial maneuvers are central to this. The protracted debt restructuring processes in Zambia and Ghana — navigating between traditional creditors, new bilateral lenders like China, and private bondholders — are brutal exercises in sovereign financial statecraft. Each negotiation, as tracked by institutions like the World Bank, builds technical capacity and shifts the balance of expertise, gradually empowering debtor nations to set more favorable terms for their future in the global economy.

Africa’s repositioning from the margin to the center of the geopolitical imaginary is therefore real but must be viewed without illusion. It does not signify emancipation. Debt vulnerabilities remain acute, climate impacts are devastating, and elite capture of geopolitical dividends is a persistent risk. Strategic competition can empower authoritarian leaders, and new partnerships can replicate old extractive logics. However, to focus solely on these continuities is to miss the transformative shift. Africa is no longer just a subject of geopolitics; it is an authoring agent, however constrained. Its territories are the testing grounds for new global orders, its markets are battlegrounds for competing capital, and its young population is shaping global culture and labor. The continent has moved from being a passive object on the map to being a complex of active, negotiating subjects. The margin has not been erased, but it has decisively moved, re-centering the global map of power, relevance, and possibility in ways that will define the rest of the century.

Recalibrating global engagement with Africa requires moving from symbolic inclusion to genuine co-authorship of the international order. Creditor nations should back a UN-led sovereign debt restructuring framework with all lenders and Climate Debt Clauses, to suspend repayments after climate disasters, preventing austerity-driven setbacks. Western powers must advance the Ezulwini Consensus and secure permanent African seats on the UN Security Council, enabling Africa to shape global rules rather than merely operate within inherited frameworks. Economic partnerships should prioritize regional green industrialization under AfCFTA, building “mine-to-manufacture” ecosystems that retain value, develop technological capacity, and expand skilled employment.

Security cooperation must be transparent and accountable, strengthening the African Standby Force through joint oversight and capacity-building. Migration policy should adopt ethical reciprocity, guaranteeing labor rights, family reunification, and skills investment in countries of origin. Decolonizing the geopolitical imaginary further requires support for African research networks such as CODESRIA and secure digital infrastructures. Finally, the COP27 Loss and Damage Fund must be rapidly capitalized, governed with strong African leadership, and channel resources directly to community-based adaptation initiatives to ensure accountability, equity, and locally driven priorities.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Magazine and its editorial team. Views published are the sole responsibility of the author(s).